The Birth of "Good Times" : A Summer of Musical Revolution

The Birth of "Good Times” : A Summer of Musical Revolution

It was June 4th, 1979, a sweltering afternoon in East Elmhurst, Queens. The sun beat down mercilessly on the concrete jungle, creating shimmering heat waves that danced above the asphalt. I had just trudged home from junior high school, my backpack slung over one shoulder, sweat beading on my forehead. As I approached our home, the muffled sound of music grew louder with each step. The moment I opened the door, I was hit with a wall of sound - the unmistakable voice of Frankie Crocker booming from the radio on WBLS.

Frankie Crocker, the "Chief Rocker" of WBLS, was a legend in his own right. His smooth, charismatic voice had been the soundtrack to our lives for years. As I stood in the doorway, letting the cool air from the window fan wash over me, I heard him announce with his signature flair, "Here is Chic's latest single, 'Good Times.'"

The bassline dropped, and I felt it in my chest before I even realized what I was hearing. It was like nothing I'd ever experienced before. When Bernard Edwards' solo kicked in, I nearly lost my mind. The intricate, funky bass lines seemed to defy physics, creating a groove so infectious it was almost tangible. Nile Rodgers' guitar licks danced around Edwards' bass, creating a sound that was both sophisticated and irresistibly danceable. The interplay between these two musical geniuses was nothing short of magical.

As I stood there, transfixed by the music, I couldn't help but move. My feet started tapping, my head bobbing to the rhythm. The lyrics, inspired by Milton Ager's "Happy Days Are Here Again," spoke of celebration in the face of economic hardship. It was a message that resonated deeply in our neighborhood, where times were often tough but spirits remained high.

"Good times, these are the good times. Leave your cares behind, these are the good times"

The words seemed to float on the air, carried by the silky smooth vocals of Alfa Anderson and Luci Martin. Their voices blended perfectly with the instrumental, creating a sound that was at once nostalgic and futuristic.

Over the next few weeks, it became clear that "Good Times" wasn't just a hit - it was a phenomenon. Soon, the entire neighborhood was hooked. Every block party, every gathering, "Good Times" was the anthem that united us all. It was as if Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards had tapped into the collective consciousness of a generation seeking escape and joy.

I remember vividly the first block party after "Good Times" dropped. The street was alive with energy, people of all ages coming together to celebrate life and music. As the sun set, casting a golden glow over the festivities, someone put on "Good Times." The reaction was electric. People who had been sitting in lawn chairs jumped to their feet. Kids stopped their games to dance. Even the older folks, who usually kept to themselves, were nodding along with smiles on their faces.

My buddy Ruff, who spent weekends in Harlem working at his grandmother's shop, brought back a cassette tape one day. His eyes were wide with excitement as he told me about what he'd heard in Harlem. We huddled around his boombox in his cramped bedroom, the anticipation palpable. When he pressed play, I heard something that would change my life forever.

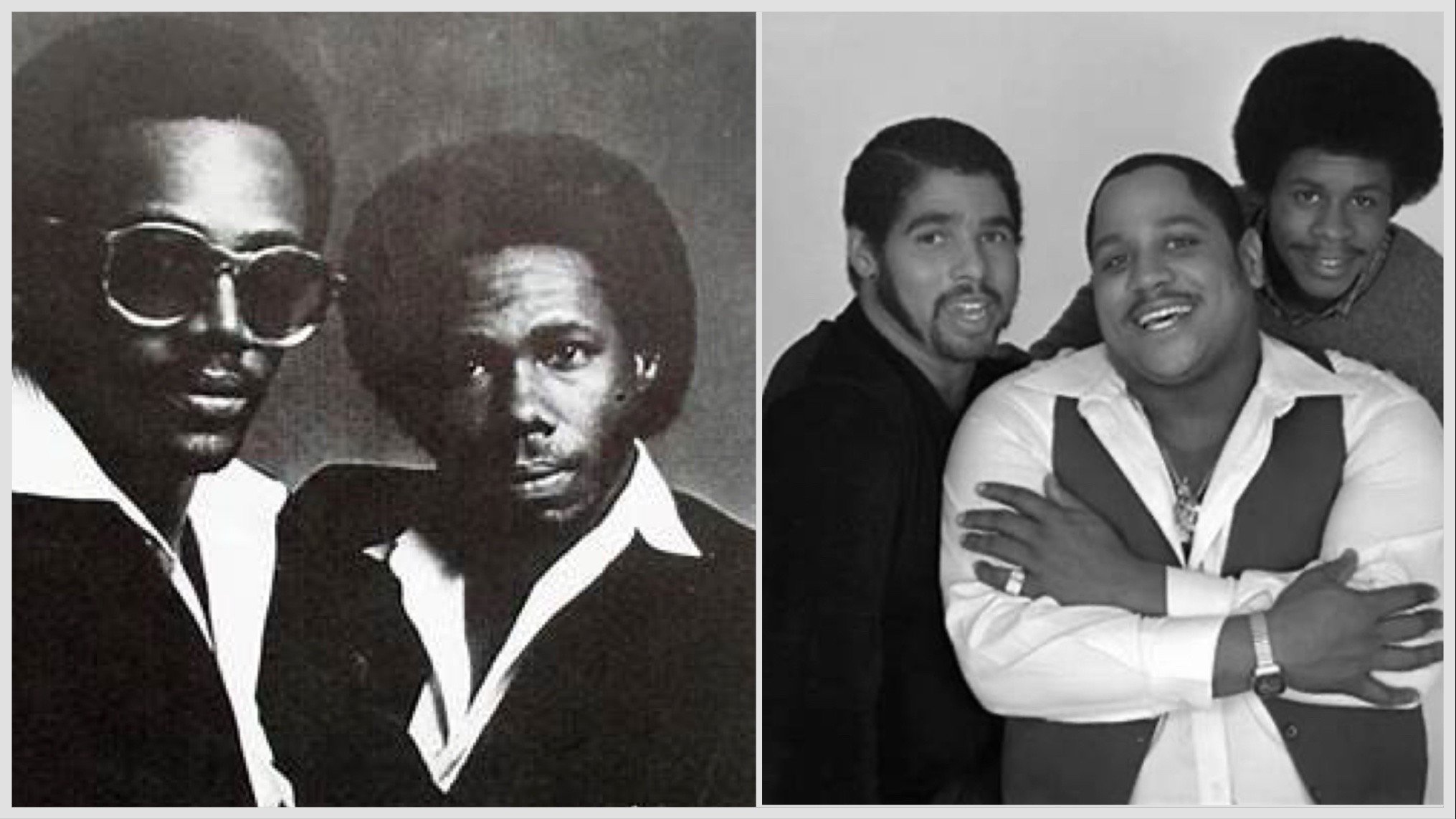

It was Melle Mel, rapping over "Good Times" while Grandmaster Flash cut the record. The way Melle Mel's words flowed over the beat was unlike anything I'd ever heard before. "Not a butcher or a baker or a candlestick maker," Melle Mel's witty line stood out like a beacon, showcasing his lyrical prowess. The Furious Five were on fire, but Melle Mel and his brother Kid Creole's voices dominated the track, their energy and charisma undeniable.

As we listened, Ruff and I looked at each other in awe. We knew we were witnessing something special, something revolutionary. Little did we know then that this moment was the birth of a new genre that would go on to dominate popular culture for decades to come.

The next morning, I couldn't contain my excitement. I bolted out of bed, threw on my mock neck, Kangol hat, bell-bottom Lee jeans, and British Walker shoes, and hurried to Wally's Record Shack on 93rd Street and Astoria Blvd. The shop was a haven for music lovers, its walls lined with vinyl records and posters of legendary artists. The smell of vinyl and old paper hit me as I walked in, a familiar and comforting scent.

"Yo Wally," I called out, slightly out of breath from my rush to get there. "Let me get two copies of the 'Good Times' 12-inch single." My excitement was barely contained, and Wally, a middle-aged man with a receding hairline and kind eyes, chuckled at my enthusiasm.

As he went to fetch the records, my eyes roamed the shelves. I also picked up "Frisco Disco" by Eastside Connection and "Scratchin'" by The Magic Disco Machine. "Frisco Disco" was a vibrant, colorful vinyl that caught my eye, while "Scratchin'" was a record I knew needed to be sped up to 45 rpm to make it funky enough for an MC to rap over. But "Good Times" was the main attraction, a record that seemed to hold the promise of endless summer nights and new possibilities.

As I left the store, clutching my precious vinyl, I couldn't have imagined the impact this song would have. It would go on to inspire countless artists, from Queen to Blondie to Daft Punk, becoming one of the most sampled tracks in history.

The following day, I went to Ruff's for a DJ battle in his basement. The air was thick with anticipation as DJ Mark “DJ” Wiz Eastmond and the rest of the crew gathered, ready to take on John Levy and his team. The stakes were high: the winning crew would take the loser's equipment and their best DJs. It was a high-stakes game in our world, where gear was expensive and hard to come by.

We lined up, each with a record in hand, ready to cut and scratch on the turntables. Our setup included two Technics SL-B1 Belt Drives and a Numark Mixer, the tools of our trade. The basement was dimly lit, adding to the tension in the air. The smell of sweat and excitement mingled with the musty scent of the underground room.

When it was my turn, I took a deep breath, placed my hands on the turntables, and threw on two copies of "Good Times." The moment the needle hit the record, magic happened. I manipulated the tracks, creating a new rhythm out of the familiar beats. My fingers moved almost of their own accord, cutting and scratching with a precision I didn't know I possessed while isolating the break section of the records.

The crowd erupted, their cheers drowning out the music for a moment. As I stepped back, breathless and exhilarated, I knew we had won the battle. "Good Times" was our secret weapon, the track that sealed our victory. John Levy's crew looked defeated, but there was respect in their eyes. They knew they had witnessed something special.

A month later, I was in my bedroom, the radio playing softly in the background as I did my homework. Suddenly, I heard something that made me drop my pencil and turn up the volume. Three guys were rapping over the instrumental of "Good Times." It was different from anything I'd heard before. They were rhyming over the track, passing the mic back and forth like park MCs, but this was on the radio!

I later learned that this was "Rapper's Delight" by the Sugarhill Gang, a track that would go on to become hip -hop's first mainstream hit. I couldn't believe it—rap records were becoming a thing. Soon after, many MCs emerged, making rap records and pushing the boundaries of what music could be. The landscape of music was changing before our very ears, and "Good Times" was at the heart of it all.

As the years passed, I never lost my love for "Good Times" and the music it inspired. I followed the careers of Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards, marveling at their continued influence on the music industry. Their production work with artists like David Bowie, Madonna, and Duran Duran showcased their versatility and genius.

Their innovative spirit inspired me as a record producer, leading me to sample tracks from Nile's catalog, which turned out to be a huge success for me. Songs like Puff Daddy’s "Been Around the World," featuring Mase and The Notorious B.I.G., and Faith Evans' "Love Like This" became staples in my repertoire. Even the remix of "Be Faithful" by Fatman Scoop achieved significant acclaim, further solidifying my connection to the legacy of "Good Times." Each project was a testament to the timelessness of Nile's sound, proving that the grooves of the past could still resonate in the modern music landscape.

Almost 20 years later, in the late '90s, I had the incredible opportunity to meet Nile Rodgers at a friend's home in Los Angeles. Cathy Jones, a mutual acquaintance, had a meeting with Nile, who was launching his own distribution company. It was a bold move, considering most people in the music industry were taking the traditional route.

As I shook hands with Nile, I was struck by his warmth and humility. Here was a man who had shaped the sound of popular music for decades, yet he spoke to me like an old friend. We hit it off immediately, bonding over our shared love of music and its power to bring people together.

Nile told stories about the creation of "Good Times," how he and Bernard had been inspired by the economic recession and wanted to create a song that would lift people's spirits. He spoke about the technical aspects of the recording, the specific guitar he used, and how they achieved that iconic bass sound. It was like getting a behind-the-scenes look at the creation of a masterpiece.

As our conversation flowed, Nile invited me to one of his studio sessions in Manhattan. I couldn't believe my luck. The next week, I found myself in a state-of-the-art recording studio, watching Nile work his magic. After all these years, his passion for music was undiminished. He approached each session with the same enthusiasm and creativity that had made "Good Times" a hit two decades earlier.

Watching Nile in the studio was a masterclass in music production. His attention to detail, his ability to bring out the best in the artists he worked with, and his innovative approach to sound were awe-inspiring. As I sat there, I couldn't help but think back to that sweltering day in June 1979 when I first heard "Good Times" on the radio.

The journey from that afternoon to this moment in the studio with Nile Rodgers was a testament to the power of music to shape lives and create lasting memories. "Good Times" wasn't just a song; it was a cultural phenomenon that brought people together and inspired a generation. It had been the soundtrack to block parties, DJ battles, and the birth of hip-hop. It had crossed genres and generations, its influence still felt decades after its release.

As I left the studio that day, the opening chords of "Good Times" playing in my head, I realized that the good times weren't just in the past. They were here and now, in every note played, every record spun, and every new artist inspired by the legacy of songs like "Good Times." The music lived on, its spirit as vibrant and infectious as ever, continuing to bring joy and unite people across time and space.

During one of our conversations, Nile shared a story that shed light on the complex world of music rights and royalties. He told me about the time when he and Bernard first heard "Rapper's Delight" by the Sugarhill Gang. The track, which heavily sampled "Good Times," had taken the world by storm, but Nile and Bernard hadn't seen a dime from it.

"We were shocked," Nile said, his eyes reflecting a mix of disbelief and determination. "We knew we had to do something about it."

Nile explained how they decided to sue Sugarhill Records. It was a bold move, especially considering how new and undefined the concept of sampling was in the music industry at the time. The case never made it to court, though. They settled out of court with Sugarhill Records, a decision that would have far-reaching consequences.

What struck me most about Nile's story was what happened next. He and Bernard learned that the Sugarhill Gang rappers were broke. Despite the massive success of "Rapper's Delight," they hadn't seen any royalties from the label.

"We couldn't just leave it at that," Nile said, his voice filled with empathy. "Those guys had created something revolutionary, even if it was based on our music. They deserved something for their contribution."

In a move that spoke volumes about their character, Nile and Bernard decided to share their settlement money with the Sugarhill Gang. They cut a check for $50,000 for each member of the group.

"You should have seen their faces," Nile chuckled. "At the time, that was the most money any of them had ever seen. It was more than Sugarhill Records had ever given them."

This act of generosity not only helped the struggling rappers but also highlighted the often exploitative nature of the music industry. It was a reminder that behind the glitz and glamour, there were real people struggling to make a living from their art.

As I listened to Nile's story, I was struck by the complexity of the music world - the interplay of creativity, business, and ethics. "Good Times" had not only revolutionized music but had also played a part in shaping the legal and ethical landscape of the industry.

The story of "Good Times" was more than just about a hit song. It was about the birth of a new genre, the fight for fair compensation, and the power of music to bring people together. It was a testament to the enduring spirit of creativity and the unexpected ways in which art can impact the world.

By Ron Lawrence